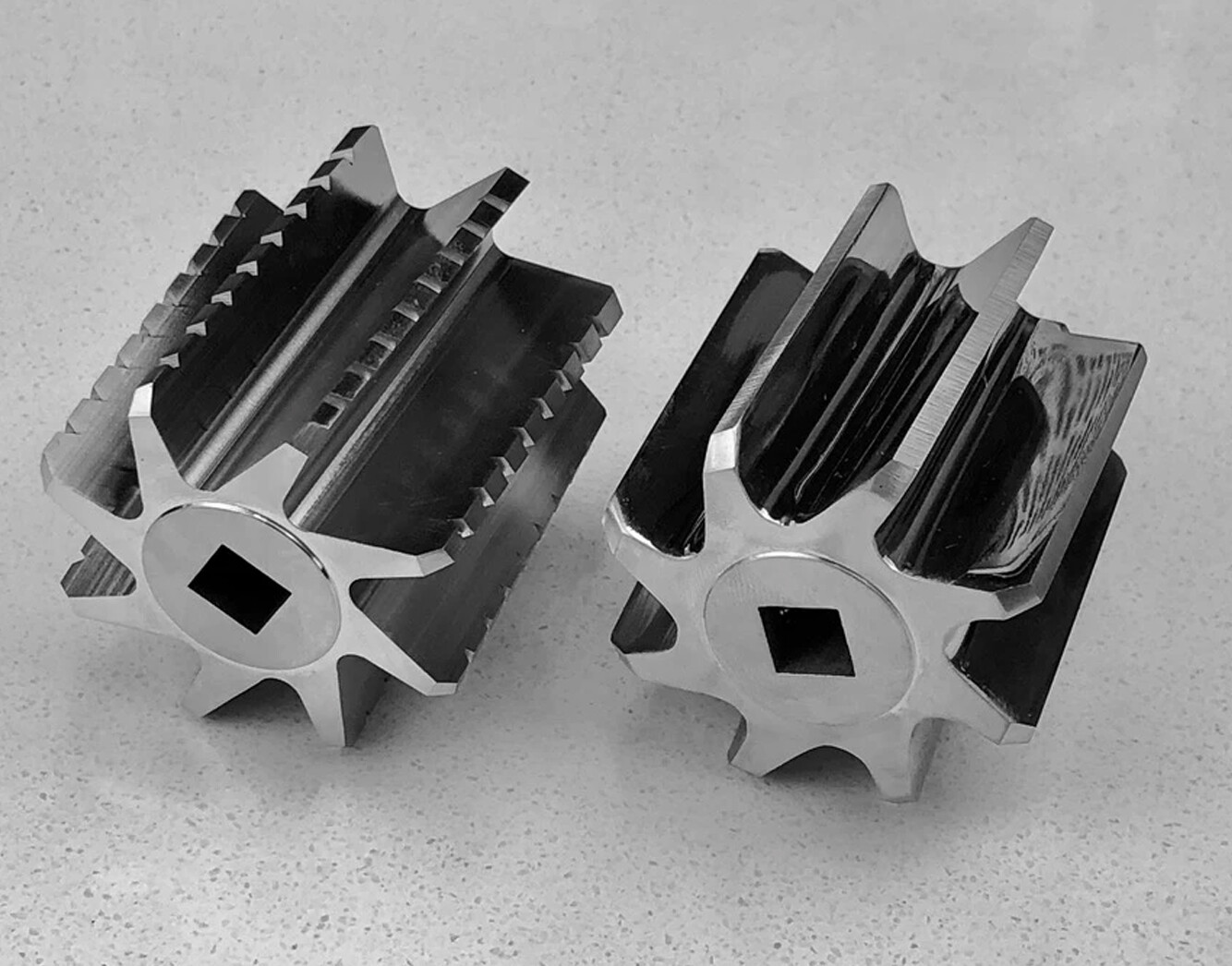

By David Feinberg, Founder & CEO of PURE Juicer

Bee space, my time with the bees.

There is a fundamental concept in beekeeping, bee space.

This is the optimum distance between two surfaces in a beehive essential for the normal movement and functioning of bees. Too small, and the workers fill it with propolis and too large, they fill it with honeycomb. First documented in Europe in the 1800’s I like to joke that, “bees are metric” because bee space is approx 1 centimeter.

Bees are mysterious.

Often feared as stinging insects, or misunderstood as a threat when a swarm lands in search of a new home.

Yet, bees are a perfect model of an ideal culture. They truly are one for all, and all for one. Clean and organized, they freely provide their service – pollination and they make a product, honey that everyone wants and only they can make. To this day, there is no such thing as man-made or synthetic honey, only bees make honey.

Bees are magical too.

Once a day the colony dissolves from a single organism about the size and weight of a cat to become 30-40,000 individuals spread over the neighborhood with a single purpose to collect nectar, pollen, and propolis. At sunset, they come home and reassemble back into a single entity. Part of the magic is that simultaneously, they are both individuals and members of a super-organism.

Every bee in the colony including the queen has a job.

The queen’s job within the colony is to regulate their purpose and to lay all the eggs. She is the sole mother to the colony and a worker among workers.

As long as she is fertile, her pheromone scent is strong, she stays queen of the colony. When she ages and her scent weakens the colony temporarily re-takes control and makes a new queen to replace (supersede) her. The colony will also make a new queen when the colony is thriving and has sufficient resources to swarm (reproduce).

How do bees communicate?

Primarily by smell and a unique dance. Bees use smell as their language; they communicate with pheromones. There are many scents: a brood pheromone for the eggs and larvae to encourage feeding. There is a special, “come hither” pheromone to say to a landing swarm, “this is where the queen is”. An attack pheromone, that smells like rotten bananas, that says, “sting the intruder”, and a queen pheromone that says I’m here and healthy, “everything is ok”. The other way bees communicate is they dance in the dark to tell each other where to find food, water, and colony resources. This dance is called the circle or waggle dance. By dancing on the comb they tell other foragers, where, how far and how abundant the supply is.

In season, queen bees lay 3,000 eggs per day.

They create a brood nest that is the heart of the colony. It is a layered soccer/basketball sphere of bees. At the center of the brood are the female worker bees, the worker brood is carefully maintained at 93.7F. Surrounding the worker brood is the drone brood. The drones are surrounded by a thin sphere of pollen, and the pollen is surrounded by a sphere of honey, this is called the honey arch.

While queen bees get a lot of attention, the real stars of the hive are the worker bees.

From the moment they emerge from their cells, worker bees begin the first of their many jobs within the hive. To get a better understanding of how the colony works together to support itself, it’s essential to know more about the jobs of the worker bees. Although they only live for about 42 days in the busy season, every day is packed with activity to prepare the hive for the upcoming winter.

The Many Jobs of the Worker Bee

The best way to learn about the many jobs of a worker bee is to start at the beginning! Let’s follow the worker bee throughout her life and learn about the many different roles she will hold in the colony.

After the queen lays an egg, it takes about 21 days for the egg to mature into an adult worker bee. Young worker bees start as house bees, tending to the many duties inside the hive. About halfway through their lives, they venture out of the hive to begin their fieldwork as foragers.

Beehives.

Beehives are some of the most naturally sterile environments. Young worker bees help to keep it this way in a few different ways. Their first responsibility is to clean their birth cells to prepare them for the next egg or stores of nectar and pollen. They will also clean nearby cells to keep things moving efficiently.

These young bees are also undertakers, some become responsible for removing any dead bees or larvae that did not mature into adult bees from the hive. They do this to prevent any disease that could put the whole colony in danger.

Nurses (Days 4 to 12).

The next role of the worker bee is to care for the larvae and young drones. They will feed the larvae royal jelly, pollen, and nectar, visiting each cell about 1,300 times each day. Worker bees also groom, feed, and clean up after the drones until they are old enough to care for themselves.

Queen Attendants (Days 7 to 12).

Like true royalty, the queen bee needs attendants to help her take care of her basic needs. She is busy after all, laying up to 3,000 eggs a day! Worker bees aid the queen by feeding, grooming, and cleaning up after her. They also help to spread her unique pheromone, signaling to the rest of the hive that the queen is still alive and well.

Pollen and Nectar Collectors (Days 12 to 18).

When the foragers return to the hive with their hauls of nectar and pollen, house worker bees are ready for action. Their job is to transfer the new resources from the foragers to their designated cells. Worker bees will add enzymes to the nectar to help ripen it and prevent it from spoiling.

Air Conditioners (Days 12 to 18).

One of the most important jobs of a worker bee is to control the temperature within the hive. Known as fanning, the workers will flap their wings vigorously to increase the flow of air and reduce humidity. Other bees will provide water to the fanning bees to help in the cooling process.

They also fan their wings to evaporate water from the honey until it is the right consistency to stay fresh over the winter.

Wax Makers (Days 12 to 35).

Older worker bees begin to produce wax from glands in their abdomens. The glands produce small flakes of beeswax that the bees chew until it is the right consistency. The beeswax is used for making new honeycomb cells and capping those that contain honey and larvae.

Guards (Days 18 to 21).

Before going out into the field, a worker bee will take on guard duties. Their job is to stay near the entrance to the hive and prevent unauthorized visitors from intruding. How can they tell if a bee does not belong? Guard bees use their sense of smell to detect when a bee is from another colony.

Foragers (Days 22 to 42).

Finally, the worker bee can emerge from the hive! Foragers visit flowers, usually about 100 flowers on a trip, to collect pollen and nectar. The bees will often travel several miles away from the hive to find the best food sources. Upon returning to the hive, they drop off their wares to younger worker bees who transfer the nectar and pollen to an open cell.

The Hardworking Worker Bee.

From the day that they are born, worker bees play a huge role in the hive. They act as housekeepers, nurses, and assistants, all before they are two weeks old! As you can see from the many roles that they hold throughout their lives, they aren’t called workers for nothing.

There are two types of queens.

Swarm queens and supersedure queens. When there are too many bees and too much abundance (pollen and honey) the workers know it is time to reproduce and create a new colony so they create swarm queens.

These are queens whose future job is to lead the colony after her mother sets off in the heart of a swarm to start a new colony. When the bees make swarm cells, they are usually placed next to the drones on the margin of the brood nest. On cold nights and the colony contracts to protect the worker brood, they’re saying, we can afford to sacrifice drones and swarm cells but we must protect our most valuable members, the future workers, and the queen.

The other type of queen is a supersedure queen.

This is when the colony creates a new queen to replace a failing queen. In the brood nest, the bees prioritize supersedure queens over swarm queens because the life of the colony depends on her. The workers place these queen cells right in the center, the warmest part of the brood nest. This is the safest and most important location in the hive.

They vote to make new queens, they vote to swarm and they vote when swarming where on which home they will move into. To swarm, workers vote by starting to make queen cells, the long peanut-shaped cells queens are raised in, and the workers vote by adding and subtracting flakes of wax from their abdomens. If more workers add wax, the cells are completed and a queen is raised.

How do bees reproduce?

When bees swarm they are dividing themselves from one colony into two. The mother queen leads half the colony away to start a new one. Up till now, she has been pampered and fattened up so she can lay 3000 eggs a day, now the mother queen is put on a diet and made to exercise so she can get down to flying weight. To do this, the workers chase her all over the combs and around the hive, they feed her less, and when she is light and strong enough to fly, on a sunny spring afternoon, she is pushed out the front door into the midst of the swarm! Queens don’t get to vote, only the workers do.

Bees vote, finding a new home.

The swarm then lands on a nearby fence, tree, bush, or sometimes even a person and sends out scouts to look for a new home. When the scouts come back they dance the location for the other scouts, when enough scouts all dance the same spot, the bees depart and fly to their new residence. At home, there are unhatched queen cells and soon a new queen will emerge and be raised to head the colony.

My bee story starts with my wife Sarah.

About 20 years ago, Sarah brought a colony of bees home. By chance, I became fascinated with them and took over husbanding the colony. Over the years, they have changed my life, this is that story.

Sarah is all about nurturing people and animals. She is all about biology, the nitrogen cycle, and ants (another eusocial insect). Ants are her favorite but she loves and respects all life forms. The two most profound animal insights she has taught me are:

- We don’t own pets, we purchase the right to take care of them.

- Animals live for their own pleasure, not ours.

With these two ethical guides, it is possible to make almost any decision regarding the care and treatment of animals.

Introduction to beekeeping.

It was 4:00 am, Sarah was shaking me awake, time to wake up. We had a date to help move 30 colonies, about 1,000,000 bees from the Puget Sound lowlands to high on Mt Rainier. We had been invited to help move his bees to feed on the fireweed. Frank kept bees on farms and rural properties near Seatac airport. This land is now buried under what is now Runway Three, back then it was farms and backyards.

I had no idea what I was in for, nor did I own bee gear.

Frank had a suit for Sarah but I wore a Gore-tex jacket, welding gloves, and rubber boots. Before dawn, we drove with Frank to collect his hives. These were monster colonies, taller than I and bulging with bees. We strapped them together and lifted them into his flatbed truck and headed for the fireweed. The day turned out to be in the 90s, it was brutally hot in my outfit.

When we got to Mt. Rainier, we built an electric corral for the bees, to keep the bears out.

Then we unloaded the bees. At this point, the colonies had been sealed up all day during the drive. By the time we unloaded them, they were hot and feisty after a day on the back of a truck and ready to fly. When we let them out, they came out in a boiling cloud of unhappy stinging insects. It was so intense, that I had to walk away.

Fireweed

For several years, I kept one colony.

Often it did not survive the winter, and I would start over in the spring with new bees. This happens a lot and to many beeks (beekeepers). One year, I decided I wanted to learn more and do better, I got four colonies. This was the year I truly started learning from the bees. When you have more than one colony, you can see the difference in colony vitality and begin to see the differences between queens and colonies. Plus, you can move frames of bees or food between colonies to balance and reinforce them. For me, this is when I had my, “aha”, moment. In the following years, I raised more and more colonies. One year I ended with between 60-70 colonies spread over four apiaries.

Raising queens, I wanted to learn more.

I signed up for a weekend class, taught by Sue Cobey, a leading queen bee geneticist. The class was given at UC Davis in California’s central valley. I got the last spot in the commercial beekeepers’ group. A blessing in disguise to see it from their viewpoint. I had signed up for the amateurs but this was the only available slot, my heart was set on learning how to raise queens. It was there I met my beekeeping mentor.

What’s it like, having so many bees?

It’s a job, but a great job. The goal is to build all the colonies up to surplus honey and to have them matched in size and vitality. This way on a given day, they are all about the same, and the same management is performed on all. Upon inspection, they’re all equally developed and the same activities are taking place in all colonies. But it never happens like that, there are always small colonies called, “dinks”, production colonies, and monster colonies. This is part of the adventure and the thrill of beekeeping.

Keeping bees is my refuge and relaxation, I do this for myself.

In the queen class, Sue encouraged us to try not to wear a veil and protective covering. At the time I was too afraid not to have at least a veil. Now my preferred outfit is little or no protective gear. I assure you I have no death wish. Rather, there is a zen aspect to beekeeping and the freedom of being au natural with the bees is deeply satisfying. Suits, gloves, and veils separate us from the experience of being at one with the bees.

Over time, bees have become predictable and known.

I know I can open a colony from early March to the beginning of August without fear. I know what a healthy colony looks, smells, and sounds like. I can tell at a glance if they are queenless or queenright. By smell, if they are content or defensive, by sound if they are tired of my intrusion into their space.

Imagine, standing unafraid in a cloud of bees, and feeling the wind from their wings on your face, their little feet as they land and walk on you, the elusive scent of different types of honey drying in the hive? Not having to see through a veil but to remove that which separates us from the experience?

I used to move my bees to follow the bloom.

Now, my bees are stationary, I no longer move them to chase a varietal honey crop. I have come to believe that the fewest number of interventions and management manipulations I do equals the least stress on the bees. The lower the colony stress the healthier the colony. Plus, the honey from stationary hives tastes better.

I do harvest honey but I don’t keep bees for the honey, I keep bees for the pleasure it provides me for the bees to thrive under my care. To figure out what works and what does not? To relax in this special space. With the bees, I am answerable to no one, just the bees. Because my goal is the healthiest bees possible my management choices are focussed on colony health – not honey.

People say my honey is the best they have ever tasted. I’ll take the compliment but think, all real beekeeper honey tastes very different from store-bought honey. Store-bought honey is usually a single source varietal or generic clover honey. I take honey only once a year. This way the harvested honey is a record of last year’s bloom cycle. It is multi-floral, with dozens of nectar sources and hundreds of pollen inputs, this makes complex and nuanced honey. It’s a reflection of where I live and also an amazing taste.

I no longer purchase bees, most of my colonies successfully overwinter, what loss I do have is made up by collecting spring swarms. I do buy supplemental queens in spring and fall to help start new colonies.

Spring is the most fun.

It’s when colonies are building up, queens are mating, swarms are happening and the colony is building up for the nectar flow. The bees are the happiest and frames can be pulled bare-handed for inspection. Come the late summer and dearth, I tend to leave them be and not risk getting stung.

Thank you for letting me tell my story and describing bees and bee behavior.

Never in my wildest dreams did I consider being a beekeeper, nor a parent, husband, or maker of juicing machines. We have a path in life and our purpose is to discover our path. We don’t always know what we are supposed to do, or what is right but if we listen, see and smell with the same intention we enter a hive of bees or a lion’s den, and we can find our path and walk toward our destiny.

It’s sunny now and time for me to head out and tend some bees…..thank you sharing the journey.

David Feinberg

Founder and CEO of PURE Juicer

And owner of Several Gardens Farm

More about our Puget Sound Beekeepers Association

Terri Lucrisia says:

FASCINATING! STORY….David YOU are one of the most interesting human I have had the privilege to know! Keep up the phenomenal work! GOD BLESS